The scene begins with a man theatrically putting on a white lab coat, matching mask and transparent protective glasses before adjusting his left glove with a dramatic snap while an array of beakers bubble in the background. The camera then pans to a large number of flasks of various colors and a set of empty test tubes before drifting back to a shiny round beaker filled with honey-colored water furiously rotating on a centrifuge as the sound of effervescent liquid fills the air. The viewer then encounters an anonymous man in a white lab coat who carefully (and rather pointlessly) transfers non-descript pink liquid from one beaker to the other. At this point a lady enter the lab and cheerfully chimes in with: “Aap lab main kya bana rahay hain?” (What are you preparing in the lab?), to which the man, turning his face away from the colorful apparatus, confidently responds: “Hum Pakistan ka paani saaf karnay ki koshish kar rhay hain” (We are trying to clean Pakistan’s water). As he continues fiddling with the complex looking equipment, the woman fires another query, “Science ka shawk kab say hua?” (When did you become interested in science?), “Abhi abhi” (Just now), responds the man as he now pours out liquid into another beaker.The year is 2019 and the man in question is none other than Fawad Choudhry, the face that launched a thousand memes, the current Federal Minister of Science and Technology of the sixth largest country in the world in terms of population, the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

This then, is what our Minister of Science & Technology believes the process of scientific inquiry ought to look like: an array of beakers, centrifuges and bubbling colorful liquids being mixed together in a poorly-lit lab by a man, who looks every bit the part of a ‘mad scientist’, with a newly- acquired and abiding love for science. And what about the goal, you ask? Well it’s nothing short of cleaning Pakistan’s water. This is the man who we are meant to follow as he takes us and our science into the 21st century — and plans Pakistan’s virgin expedition to outer space. What sort of reaction is this video meant to evoke? What is the attempt here? Is the video, meant to introduce us to the creative efforts of our Minister towards solving deep-seated problems in our society through the use of science? Or is it to show us that anyone can be a renowned scientist simply by looking the part even if the inherent skill set is missing? Fake it until you make it? Or is it meant to ridicule real and serious water related problems that Pakistan faces today and in the future? Whatever the original aim, Fawad Chaudhry eventually ends up making a mockery of himself, his Ministry and the scientific endeavor itself. For me, his video and recent statements were an unpleasant déjà vu.

In 2012, the Federal Minister for Science & Technology, Changez Ahmed Jamali, went to Sukkur, Pakistan with Religious Affairs Minister Khursheed Shah in tow, to meet Engineer Agha Waqar Ahmad, of the water kit running car fame, in the hope of replacing Pakistan’s dependence on oil imports. Waqar declared that he could run a car purely on water and went about demonstrating his water kit to all and sundry. What followed were several weeks of madness in which Agha Waqar received vociferous support from all corners ranging from television anchors, politicians, all the way to the head of Pakistan Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (PCSIR), Dr. Shaukat Parvaiz. Standing incredulously and desolately on the other side trying but failing to make the nation see reason (and the laws of thermodynamics) were Dr. Pervez Hoodbhoy, Dr. Atta Ur Rehman and Dr. Shaukat Hameed Khan.

One would have expected that the water-kit saga would have led to serious, national-level introspection. One, in which, we would have asked ourselves how it was possible that a charlatan had exposed the academic elite of the country with such alacrity and ease. And how, instead of being exposed for his fraud, Agha Waqar was eulogized and celebrated in the media. What transpired betrayed a more potent malaise, a deep-rooted anti-intellectualism at the heart of our republic and national culture.

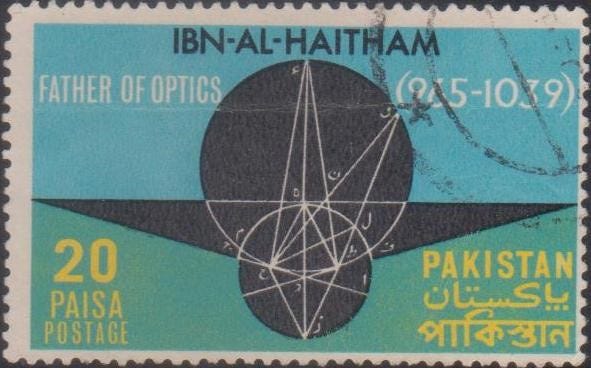

While scientific pursuit is still treated as a bit of a joke in Pakistan, there has historically been an espousal and celebration of our intellectual past, particularly our Muslim intellectual past. On Nov 4, 1969, for example, the Pakistan Postal Service issued a postage stamp commemorating and remembering the life of Ibn-al-Haitham, the medieval Arab mathematician and physics, whose legacy as the “founder of physics in the modern sense of the word” is only now being reclaimed and acknowledged.

The stamp itself draws attention to Al-Haitham’s contribution towards the field of optics. However, Al-Haitham’s lesser known, but equally significant contribution towards the scientific method, is what we could stand to benefit from even more. Rosanna Gorini describes his contribution to laying down the foundations of the scientific method in the following words: “[Al-Haitham’s] investigations [were] based not on abstract theories, but on experimental evidences and his experiments were systematic and repeatable”. Al-Haitham was a strong advocate of empiricism and took on the might of Euclid, Ptolemy and Aristotle, in his work when he went on to prove that the emission theory of light was “superfluous and useless”.

One of the most striking features of the medieval Arab scholars of that time was the acceptance and admission of their own academic and philosophical limitations and their opening up to ideas from outside. In doing so, these figures from our imagined Muslim past not only made themselves vulnerable towards different thoughts that perhaps clashed with their own, but also actively engaged in conversation with these subjects. A concerted effort and attempt was made towards translating works from all parts of the known world into Arabic. Translators of the time served not only to merely reproduce the works in Arabic, but often added corrections and commentaries to the work they were translating. It is through this rich dialogue between indigenous and transnational knowledge and the deconstruction of these ideas by Arab philosophers and scientists that people such as Ibn Al-Haitham managed to challenge established concepts.

We, as a nation, purport to follow luminaries of the past and at least claim to seek inspiration from their work. On the other hand, today, in our society, there is rampant anti-intellectualism and a certain degree of armoring up, where we shut out ideas that may attack our established dogmas and beliefs. In fact, the process of holding on to and appropriating our Islamic scientific heritage is a form of epistemological defense meant to shield us from critique about the dismal state of scientific progress within postcolonial Pakistan.

There is both a lack of admission of our own failings in terms of staying abreast with contemporary research in each discipline as well as a lack of exposure of our thoughts lest somebody catches us for the charlatans that we fear we all are. While failing to engage with these thoughts we simultaneously wrap ourselves in the comfort of the belief that if our appropriated Muslim past had not transpired, the world would not have marched towards modernity. These Muslim pasts are inextricably embedded within our national discourse on science and technology. A quick glance at the ‘About Us’ page of the Al-Khwarizmi Institute of Computer Science (KICS) in the most elite engineering school of the country, the University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore, furthers this argument. It reads: “Al-Khwarizmi’s work laid the foundations for the building of computers, and the creation of encryption in the 20th century. The modern technology industry would not exist without the contributions of Muslim mathematicians like Al-Khwarizmi.” In other words, if it were not for our Muslim predecessors, all work thereafter would have come to naught. In a sense, we are precluding ourselves of the responsibility of any further progress by stating that whatever has taken place, has done so mainly through Muslim contribution thus far. This sense of smug self-satisfaction has led to a reactionary society that fails to look inward and to introspect, that searches vainly for conspiracy theories to explain away its own self-inflicted wounds, that plays up the possibility of a world colluding to see it fail and that looks for shortcuts and miracles to extricate itself. We had begun peddling fake news in Pakistan well before the term fake news had become a commonly used term.

In fact, in Pakistan we consistently observe a suspicion of the life of the mind and of those who are considered to represent it. Being an intellectual is considered synonymous with the ability to earn degrees and with the number of years spent in the classroom alone. Learning is seen to begin and end in school, while any other intellectual pursuit, be it reading or writing, is considered extraneous and wasteful. Go to any bookstore in Pakistan, and the only books that consistently sell are school and university prescribed textbooks, i.e. material that must be bought, compulsory, as we like to say. Beyond these books, there is very little interest in reading for the sake of reading or gaining knowledge just for the sake of it. This leaves the nation holding on to the straws of intellectuals who exhibit only a skin-deep level of free and open thinking.

What is the root of this rife anti-intellectualism? Where does it stem from? Perhaps our colonial past might hold some answers. The British colonial project was primarily interested in strengthening and furthering the British hold over India. It did this partially by building a veritable civil and administrative force. The colonial project sought to ingrain within the bourgeois and the local populace the idea that prestige and honor lay in administrative and clerical duties. It developed educational institutions that mass-produced degree wielding individuals for whom the zenith of ambition meant a complete, homogeneous and servile entrenchment within the British Indian civil service. This necessarily came at the cost of emphasis on skill development, on nurturing creative intelligence and in promoting scientific disciplines. Free-thinking, idea-generating individuals would in fact have been a threat to the British stranglehold over the crown jewel. This mindset of relative prestige has persisted through to this age in the way in which a civil servant is viewed as belonging to a higher social stratum with respect to, for instance, a university professor, within our unwritten social order.

In fact, the local Pakistani intelligentsia class that succeeded the British not only eroded what little share it got of the well-oiled civil setup it received from the colonial masters, but at the same time it failed to recognize the need to realign its priorities in training the workforce by emphasizing more creative pursuits and instilling greater intellectual curiosity. It was not surprising that the brown sahibs consolidated British efforts to root out independent thought, since they saw personal gain in keeping the locals unaware and illiterate. Pakistani metropolises like Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad, as a result, have not evolved into hubs of intellectual and philosophical debate which they once showed promise of becoming.

While we can continue to analyze the roots of our anti-intellectualism at the macro level, it also pays to observe what role our domestic lives have played. It is here that children first exhibit their natural curiosity about the world around them and it is here that they depend on the environment to help them nurture their intellectual development. The home is effectively the first intellectual center of a child. According to Judith Roden, young children are natural scientists. She suggests that when children play, they explore the world in much the same way that scientists do by forming hypotheses and conducting experiments. How much they are rewarded (or punished) for these early forays into the unknown then determine how amenable they would be to exploration later in life. A conducive atmosphere in the home then remains critical in determining their natural intellectual disposition.

The causes of anti-intellectualism in Pakistan are complex and multi-variate and do not yield easy solutions. And while we may use absence of funding, resources, infrastructure as explanations for the lack of scientific progress, what we miss is more fundamental. We miss people who can exhibit critical inquiry, who can ask the right questions, identify the most important problems and go about systematically finding the means of solving them. If we don’t realize this soon, we will continue to produce ministers who want to clean Pakistan’s water in a day or want to put their bets on the same water, once miraculously purified, to run our cars.

Samee ur Rehman holds a PhD in Applied Mathematics from Delft University of Technology. He currently works as a Data Scientist in Silicon Valley, California. https://www.linkedin.com/in/surehman/

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.